The Youth Assembly launched its Big Youth Survey in January 2024. The survey was sent out to young people aged 11-21 years old in schools and youth organisations across Northern Ireland. The Youth Assembly debated the top ten topics from the survey during their second plenary in February 2024, and chose their committees based on a vote. This resulted in the formation of the Youth Assembly Education, Health, and Rights and Equality Committees.

After their plenary, the Committees met with Participation Officers from the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY). During this meeting, they focused on their committee areas to understand what areas of children’s rights were being affected in Northern Ireland.

In May 2024, Members attended a committee planning day, where they participated in capacity building workshops and activities and decided on their chosen topic of ‘Young Women’s Rights in Schools.’ In the months that followed, they examined research reports, frameworks, and studies to help inform their understanding. They also had the opportunity to link their research to the Executive Office’s Ending Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy, in particular, ‘Outcome 1: Changed attitudes, behaviours, and culture – ‘Everyone in society understands what violence against women and girls is, including its root causes, and plays an active role in preventing it.’[1]

In August 2024, the committee held a Stakeholder Day where they heard evidence from experts in young women’s rights such as policy officers from the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY), the Committee Clerk from the Committee for the Executive Office, an Assembly Research Officer, and the Director of EVAWG at the Executive Office. Later in the year, they took evidence from a school, Our Lady and St Patrick’s College Knock, and an EA Youth Voice and Participation Advisor.

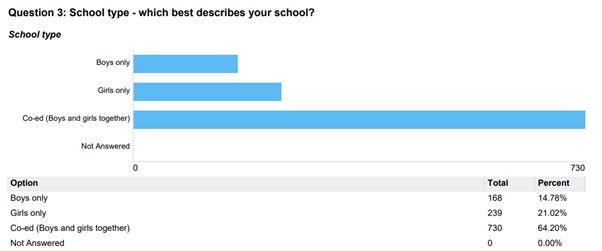

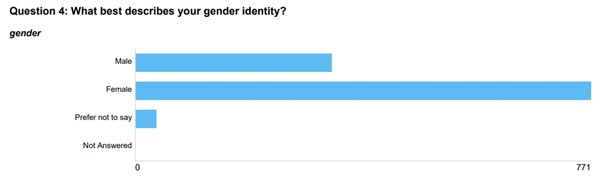

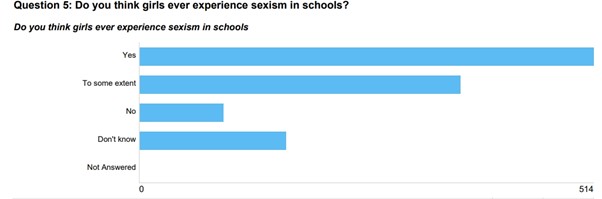

In January and February 2025, the Youth Assembly Rights & Equality Committee created a survey based on the experiences and opinions of young people across Northern Ireland. They launched their survey in early March 2025 to post-primary schools and youth organisations. The survey focused on pupils’ experience of sexism in schools, safety, stereotypes and attitudes, period dignity, uniforms, and Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE). They received 1137 responses in total.

The Youth Assembly Rights and Equality Committee are calling for schools to take stronger, more consistent action to promote gender equality and inclusion. Their recommendations include:

The Youth Assembly was established in June 2021. The current 90 Youth Assembly Members took their seats in October 2023. At the time of recruitment, they were in school years 9-12 which is approximately 12-16 years old. They are a diverse group. Membership includes young people from every constituency and recruitment was designed to ensure proportionate representation of Section 75 categories including gender, religious background, race, sexuality, disability, and young people with caring responsibilities. In addition, there is proportionate representation of young people with care experience and those in receipt of Free School Meals.

The Youth Assembly was established to perform three functions:

The Youth Assembly Members established three committees for their focus in this mandate. These are Education, Health, and Rights and Equality.

The Youth Assembly’s Rights and Equality Committee was formed in March 2024. There are two other committees in the Youth Assembly – the Education Committee and the Health Committee.

The Committees were formed following the Youth Assembly’s Big Youth Survey which asked young people, aged 11-21 years old, about the issues which matter most to them and what would they like the Youth Assembly to focus on during their mandate. The Big Youth Survey went live in January 2024 and received nearly 1800 responses from young people across Northern Ireland. The Youth Assembly debated the top ten issues from the survey:

Members voted on their top three from this list and those topics formed their committees – Education, Health, and Rights and Equality Committees.

In May 2024, the Youth Assembly Rights & Equality Committee, attended a Committee Planning Day. They participated in workshops and discussion-based activities to agree the issues which were the most pressing for them. They also looked back at the Big Youth Survey to see what other young people were concerned about. They decided to create a project on young women’s rights in schools to examine attitudes, stereotypes, and culture towards young women, as it links quite closely to the Ending Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy published by the Executive Office.

After their planning day, the committees next few meetings focused on research on young women’s rights. Please see a list below of their research and what it entailed:

Report on Sexism and Sexual Harassment in Schools, Secondary Pupils Union of Northern Ireland, 2022[1]

The Gillen Review, Department of Justice, 2019[2]

The Strategic Framework to End Violence Against Women and Girls, The Executive Office, 2024[3]

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, United Nations, 1979[4]

In August 2024, the Committee held a Stakeholder Day in Parliament Buildings, where they took evidence from experts in this area. They met with:

NICCY highlighted the distinction between duty holders and duty bearers, emphasising the responsibilities of those in power to uphold children’s rights. They outlined the relevance of the UNCRC (1989), focusing on the general principles: non-discrimination (Article 2), the best interests of the child (Article 3), life, survival, and development (Article 6), and respect for the views of the child (Article 12). The discussion also covered the role of CEDAW (1986) in supporting strategies such as Ending Violence Against Women and Girls (EVAWG) and advancing Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) in Northern Ireland. Outcome 1 of EVAWG, which aims to change harmful attitudes and social norms, was seen as closely aligned with efforts to promote young women’s rights in schools.

NICCY stressed the importance of creating space for conversations around these issues. They acknowledged the complexity of implementing RSE, noting the balance between respecting parental rights to educate their child within their cultural background (Article 29(c) of the UNCRC) and the evolving capacity of children to form and express views (Article 12(1)). The right to access reliable information, especially regarding media, was also highlighted (Article 17). Concerns were raised about young people’s safety in schools particularly for those from diverse backgrounds. NICCY emphasised the significant evidence gap in this area and called for schools to play a more active role in influencing policy. They also noted the shortcomings in proposed school uniform legislation, particularly the lack of provision for girls choosing to wear trousers. Finally, they urged young people and schools to review current policies, identify any gaps or failures in implementation, and consider the which actions which could be taken to address them.

Thomas Lough, Assembly Research Officer, discussed the importance of identifying who should be targeted in school policies aimed at tackling sexism and misogyny. He highlighted Scotland as a positive example of progress in shifting cultural attitudes within schools and the wider community.

Rebecca Potter shared her experience of establishing a pupil-led group in her school to address issues such as gendered language, uniform policies, PE kits, and period dignity. She encouraged Youth Assembly Members to take proactive steps by initiating conversations, suggesting actions such as writing to school principals, meeting with senior staff, forming activist groups, and delivering assemblies to raise awareness and drive change.

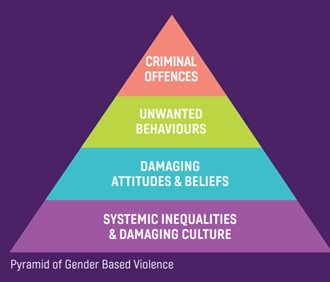

Claire Archbold, Director of EVAWG, provided an in-depth overview of the EVAWG strategy. She explained EVAWG’s theory of change using the gender-based violence pyramid, which illustrates how extreme acts like murder and assault stem from more everyday behaviours such as name-calling, upskirting, and wolf-whistling, all of which are underpinned by harmful societal attitudes and beliefs.

[1] Squarespace – Website Expired

[2] gillen-report-may-2019.pdf

Claire also shared stark statistics highlighting the scale of the issue: 4 in 5 sexual offence victims are female, 99% of imprisoned offenders are male, and 71% of women have experienced harassment in public. She also highlighted surveys showing that 1 in 2 girls had received unwanted intimate images and that 1 in 5 boys aged 16 thought online sexual comments were acceptable.

She outlined EVAWG’s five key outcomes: changing social norms and attitudes, promoting healthy relationships through RSE, ensuring women and girls feel safe, improving access to frontline services, and increasing confidence in the justice system. Claire also referenced organisations such as White Ribbon which are actively addressing gender-based violence. Finally, she encouraged young people to get involved by taking action locally, contributing to policy development, and collaborating with departments, youth services, and community groups in a joined-up approach to influence change.

After the Stakeholder Day, the Youth Assembly Rights and Equality Committee took further evidence from the following:

During the meeting in November 2024, Jamie Plant, Youth Participation Officer at EA, shared how she has supported young people’s involvement in consultations and her work with the Executive Office on the EVAWG strategy. She created workshops to build understanding, which led to a range of youth projects and the development of an easy-read version of EVAWG. On International Women’s Day, 8 March 2024, EA held workshops across Northern Ireland, reaching over 400 young people.

In the Q&A session, Jamie talked about RSE provision in schools, its inconsistent delivery, and generational gaps among teachers. She stressed the need for open conversations, especially with boys, and called for Department of Education-led policy change, as EA and CCEA have limited influence.

In December 2024, the committee met with John McCloskey from Our Lady and St Patrick’s College, Knock. John introduced his school project, Female Voices, inspired by feminist philosopher Kate Manne. He highlighted how male dominance is subtly embedded in school spaces and the curriculum, such as the exclusion of women in historical narratives and ethics courses. Observing misogynistic attitudes among male pupils, he launched a pupil-led group—with support from an all-female leadership team—to tackle sexism through research and resource development.

The group explored sexism in society and the Northern Ireland curriculum, creating materials for Learning for Life and Work (LLW) and a workshop on misogyny for Year 10 pupils. Their work culminated in a published book, Female Voices[1], launched at Parliament Buildings with MLA Kate Nicholl. They have since engaged with key education bodies and aim to develop a school policy on sexism.

In the Q&A session, John noted that it is still too early to see a cultural shift and while there has been no pushback, he stressed that real change needs formal policy. The school is open to being a model for anti-sexism work.

In January and February 2025, the committee created a survey via CitizenSpace which was promoted with youth organisations and post primary schools across Northern Ireland. There were 1137 responses from young people aged 11-18 years old. It asked questions relating to sexism in schools, uniforms, period dignity, safety and PE and sports.

The next sections will focus on a summary of their responses.

As previously stated, the survey was published through CitizenSpace, and it was aimed at young people aged 11-18 years old. There was a roughly equal split across ages 12-18. See below for a summary of age groups:

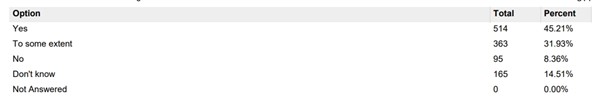

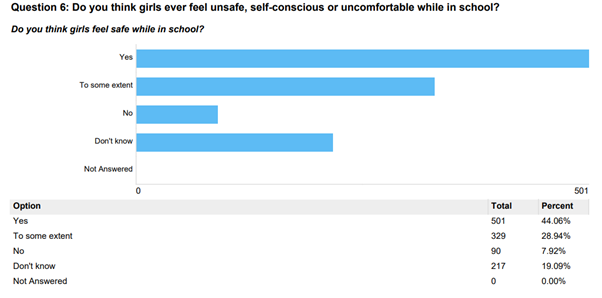

Once again, there was an overwhelming response to the question about girls feeling unsafe, self-conscious, or uncomfortable in school as 830 people responded ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent,’ which is over 73% of respondents. This would suggest that girls feel unsafe at times or others have witnessed this behaviour in school. However, there were also 90 responses stating that they do not experience this or have not witnessed this in school. Lastly, there were 217 responses stating that they were unsure.

In response to the above question, the survey asked pupils ‘if yes, please say when and where girls feel unsafe in school.’ Pupils, particularly girls, describe a troubling culture of sexualisation and harassment in schools, where unwanted advances and inappropriate jokes create an environment where many girls feel unsafe. One pupil shared,

“Boys showing unwanted feelings towards a girl to the extent where she feels unsafe.”

Alongside this, sexist jokes and attitudes persist, often dismissed as harmless banter, yet leaving a lasting impact. The influence of figures like Andrew Tate was noted, with many boys adopting misogynistic language such as telling girls to, “go back to the kitchen.”

Uniform policies further exacerbate discomfort, with girls citing stricter dress code enforcement that seems to prioritise male perspectives over their well-being. One pupil noted the unfairness, saying,

“Being told to cover up skin—skirt length is a large topic of conversation while boys can wear shorts.”

Concerns extend to teachers as well, with reports of male teachers making inappropriate comments and treating pupils inequitably. Some pupils shared unsettling experiences, including one saying,

“Male teachers make comments on skirt sizes and look under tables to check.”

Female pupils expressed anxiety about navigating spaces where they are outnumbered and subjected to degrading remarks. These experiences have deep consequences for mental health, as one pupil reflected,

“I would safely assume every girl feels insecure, unsafe or uncomfortable in school.”

Frustratingly, many believe the issue persists because it has been normalised and ignored by those in authority, with reports of misconduct often leading to no action.

“Despite reports, little was done… and there were no consequences.”

The overarching sentiment is one of resignation, with pupils feeling trapped in a cycle where inappropriate behaviour is tolerated rather than addressed.

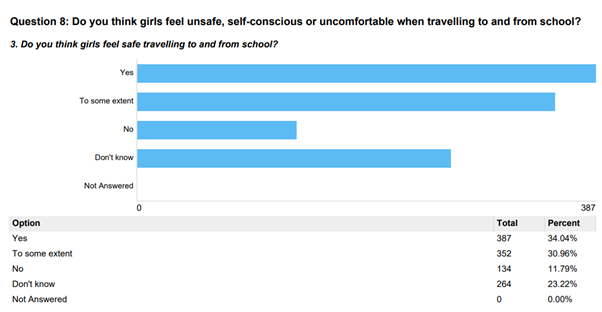

The next question focused on safety travelling to and from school and answers showed that girls feel unsafe in some form or another:

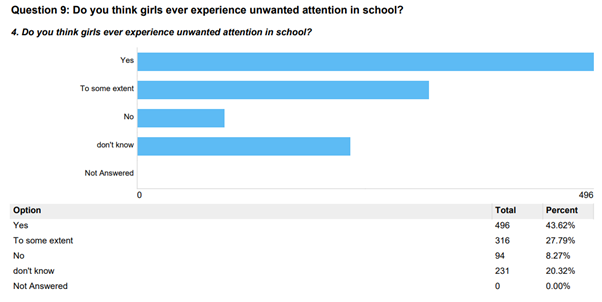

The above question examined unwanted attention towards girls in schools. Almost 72% of pupils felt that girls face unwanted attention answering either ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent.’ However, over 20% of pupils were not sure.

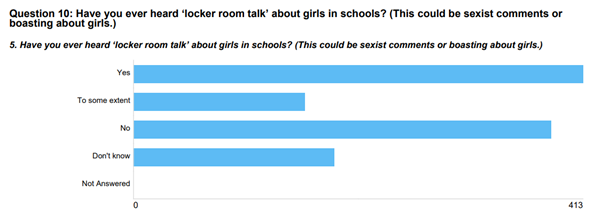

Almost 50% of pupils have experienced ‘locker room talk’ about girls in schools which could suggest that this is commonplace within schools.

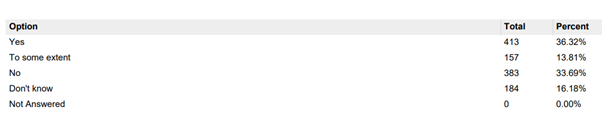

Over half of pupils have experienced teachers treating pupils differently due to their gender, whereas nearly 28% of pupils have not experienced this. Through conversations with Youth Assembly Members, they experienced this via gender stereotypes such as a teacher commenting ‘I need a few boys to help me move these tables,’ as an example.

Pupils report experiencing gender bias in schools, with teachers showing favouritisms toward boys or girls depending on personal biases. One pupil noted,

“Depends on the teacher, some favour the boys while others favour the girls.”

Unequal treatment extends to classroom interactions, where respondents stated that male teachers often give boys more attention, especially in subjects like PE. Some pupils observed,

“Male teachers actually like the boys so much better for PE.”

This favouritism also influences discipline, with reports of boys frequently receiving leniency while girls face harsher consequences. One pupil expressed frustration, saying,

“Girls are punished more harshly than boys, while boys get away with the same things.”

Academic expectations further reflect gender biases, particularly in STEM subjects where boys are encouraged more than girls. Youth Assembly Members reported that girls are often expected to be more mature but can be seen as less capable than boys.

“Teachers tend to view girls as more intelligent, but boys as more capable in STEM.”

Additionally, restrictions surrounding toilet access disproportionately affect girls, particularly in cases related to periods.

“Girls can’t go to the toilet even if they’re on their period, especially if a boy asked first.”

Gender stereotypes permeate classroom language, with remarks like, “I need two strong boys to help,” reinforcing assumptions about male capability.

Sports and physical education reveal further disparities, as boys dominate football and athletics while girls are often overlooked. One pupil noted,

“PE teachers usually don’t care about the girls – leaving them out.”

“Appearance policing” is also stricter for girls, with their uniform and grooming choices receiving more scrutiny than boys.

“Teachers shout at girls more for makeup, hair, jewellery, skirt length,” one pupil stated. Many feel that the prevailing “boys will be boys” culture excuses inappropriate male behaviour, preventing meaningful accountability.

“Teachers let the boys get away with more because of the ‘boys will be boys’ excuse.”

Finally, assumptions about subject suitability persist, with girls often overlooked in ICT and tech-related subjects. One pupil observed,

“Many teachers have preconceived ideas that boys will be better at ICT or tech.”

Collectively, these experiences contribute to an environment where gender bias shapes interactions, expectations, and opportunities in school.

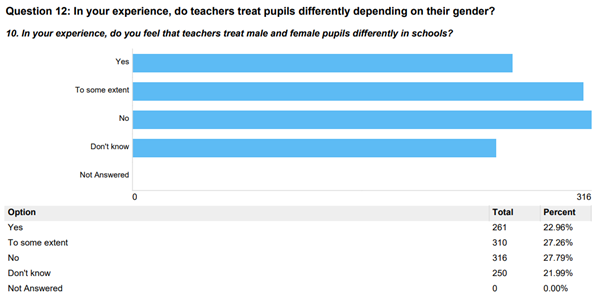

Over 60% of pupils believe that girls can approach staff about experiences of sexism as they either answered ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent’. Nearly 20% of pupils did not feel comfortable to approach staff in this manner and over 20% were unsure if they could or not.

Pupils were then asked if they had any general comments on this question.

While 60% feel girls can report incidents to someone, pupils describe a pervasive sexist culture in schools, particularly in co-educational environments, where harassment, degrading language, and gender stereotyping go largely unchallenged. One pupil stated,

“Boys need to be taught to respect girls and women, so that they know we’re not just ‘dishwashers’ or ‘kitchen dwellers.’”

Many girls report feeling unsafe due to inappropriate behaviour, such as boys pinging bra straps or making sexual comments, which are often dismissed rather than addressed. Even serious incidents like groping are met with minimal consequences, as one pupil shared,

“When I’ve received sexual comments and groping… the boy gets a call home, and I’m meant to go back to class with him.”

Despite complaints, staff responses often reinforce the problem, with many reports ignored or downplayed. One pupil noted,

“Teachers say ‘that’s just how boys act’ or ‘it’s just a joke’.”

Some pupils feel that teachers normalise sexist behaviour rather than challenge it, failing to provide protection or accountability. Pupils overwhelmingly call for reform, advocating for better education on sexism for both students and teachers. One pupil emphasised, “Proper education is needed not only for the pupils, but for the teachers as well.”

Gender-based disparities extend beyond behaviour, with respondents stating that boys frequently receive more opportunities in sports and leniency in discipline, while girls are held to higher expectations academically and socially.

“Teachers favour male pupils, and they get more sporting opportunities and McDonald’s after their rugby. We’ve not had McDonald’s yet,” one pupil remarked.

The dismissive phrase “boys will be boys” continues to excuse harmful actions, reinforcing the idea that girls should tolerate harassment.

“Violence should simply be called violence—not excused as flirting,” a pupil pointed out.

Academically, gender bias persists in subject choices and leadership opportunities, particularly in STEM fields. One pupil shared,

“Triple Award Science and Computer Science aren’t offered – staff said, ‘it won’t happen,’ even though over 10 girls wanted it.”

Even in single-sex schools, sexism remains, with rigid uniform rules and outside influences such as catcalling from boys at neighbouring schools.

“Sexism still filters in—we’re still catcalled by boys from other schools on the street.”

While some boys feel unfairly stereotyped, others acknowledge the rising influence of figures like Andrew Tate in shaping misogynistic attitudes. One pupil observed,

“Boys want to appeal to other boys. Alone, they’re fine. In groups, they put women down.”

However, many girls remain fearful of reporting sexism due to social consequences.

“Girls are seen as snitches if they talk about sexist comments,” one pupil commented.

The overwhelming sentiment is frustration—without meaningful intervention, leading many to feel that the cycle of sexism in schools will continue unchecked.

The next section of the survey examines period dignity in schools, with a focus on period products, dignity in use of bathrooms and attitudes towards periods:

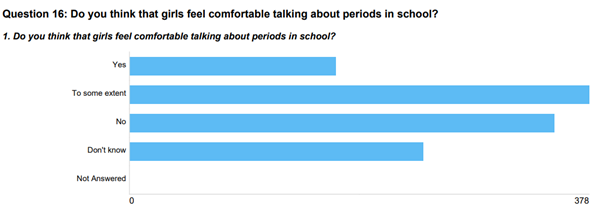

Only 15% of pupils felt that girls feel comfortable talking about periods in school. Over a third believed to a certain extent, nearly 31% believed that girls could not talk about their periods in school and over 21% of pupils were unsure. Therefore, we can suggest that girls’ experiences are varied within schools.

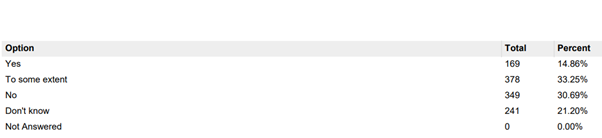

The above question focused on girls feeling comfortable asking for free period products in school. This question was chosen as the committee had many discussions around period dignity and how the word ‘period’ can still seem taboo. Once again, their answers posed a mixed response as over 44% of pupils responded with ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent.’ However, over 23% were unsure, as they did not know, which could suggest a legitimate response as they may have no experience of asking for free period products. Finally, over 32% of pupils responded ‘No.’

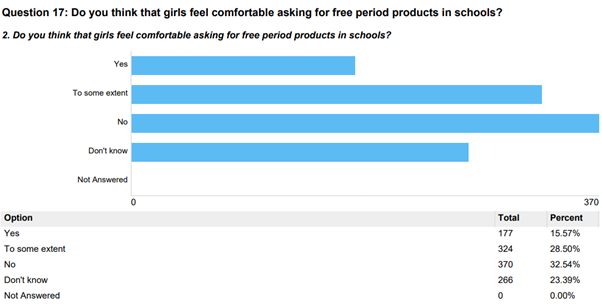

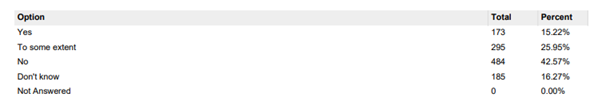

Once again, in the above question related to the ease in which girls can get out of class to use the bathroom when needed, there is a mixed response. Over 41% of pupils responded ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent,’ whereas over 16% of pupils responded, ‘Don’t know.’ Though, over 42% of pupils responded ‘No.’ This could suggest that experiences differ depending on the school, or those who answered ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’ could be male.

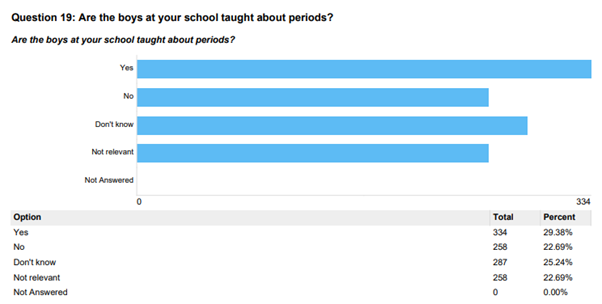

This question examined gender stereotypes in schools in relation to educating boys about periods. There is a mixed response as less than 30% stated ‘Yes’ and over 22% stated ‘No.’ Furthermore, a quarter of pupils were not sure. Those who responded ‘Not relevant’ could possibly attend an all-male school. However, this might also imply that not all boys are educated on periods.

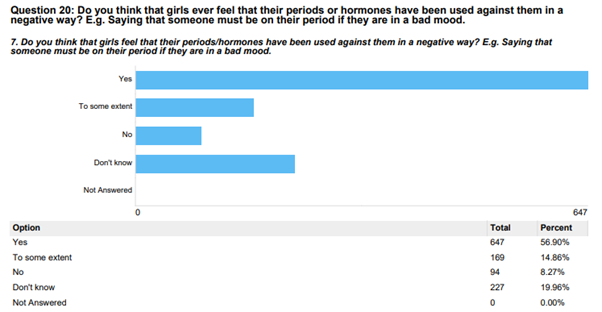

The question above examines stereotypes and attitudes towards girls and young women and over 71% of answered ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent’ when asked if their periods or hormones had been used against them in a negative way. Some pupils were unsure as nearly 20% responded in this manner and 8% responded ‘No.’ This could suggest that most girls experience this type of negative attitude towards them.

The next question asked pupils if they had any further comments on period dignity. Pupils across different school settings shared varied but consistent concerns around menstrual education, stigma, and support. In boys-only schools, many reported minimal or inadequate education on periods. One pupil noted,

“We spent more time learning about seeds germinating than puberty and periods (just a single lesson).”

Others admitted,

“I don’t know anything about this type of stuff,” or even, “I don’t know and don’t really care.”

Some expressed harmful assumptions, with one stating,

“It kind of makes sense to assume they’re on their period if they’re in a bad mood.”

In co-ed schools, many female pupils highlighted embarrassment and poor handling of menstruation. One said,

“Girls shouldn’t be forced to say they have their period out loud in order to be allowed to leave – this is embarrassing.”

Others described how boys react immaturely:

“Boys don’t take being taught about periods seriously… it’s strictly educational on biology and less about removing stigma.”

Another commented,

“Male teachers as well as females make fun of girls for being ‘hormonal’ or ‘on their lady days’.”

Some pointed out ineffective initiatives, such as,

“Our school boasts about period dignity but not once in the last year has there been a pad or tampon in the bathroom.”

However, some schools were praised:

“Our school has a period dignity team… we ensure bathrooms are stocked with free products.”

Still, pupils noted lingering shame:

“Even when restocking the toilets with period products, we act as if it is a secret or shameful.”

Many wanted male involvement, with one pupil stating,

“I wish we were able to get males involved in some way too.”

From co-ed male perspectives, some supported normalising periods:

“It shouldn’t be such a taboo topic. It is natural and happens to every girl.”

One expressed empathy:

“I genuinely wish to offer support as best I can because being an empathetic individual gives me a sense of need to help others.”

Others noted,

“People more say it as a joke to friends that are girls but would never really be malicious.”

Pupils who preferred not to say their gender, or were in girls-only schools, raised concerns about being denied bathroom access and feeling invalidated. One said,

“Girls’ emotions and feelings can easily become invalidated or ignored just because they are on their period.”

Another noted,

“Our all-girls school does a fantastic job with period dignity… but my co-ed school had no problem refusing bathroom access if the teacher felt like it.”

Overall, the responses highlight a need for improved, stigma-free menstrual education for all genders, better access to products and facilities, and more empathetic, consistent support from staff. As one pupil put it,

“Periods should be talked about… they are natural, of course. But when you’ve been taught for years to hide it, it becomes ingrained in your mind.”

The next section of the survey focused on the curriculum, mainly on Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) with a more in-depth focus on topics that could be taught to pupils; the quality of lessons; teachers’ confidence in teaching sensitive issues within RSE; the gender divide within RSE lessons; and gender stereotyped subjects within school.

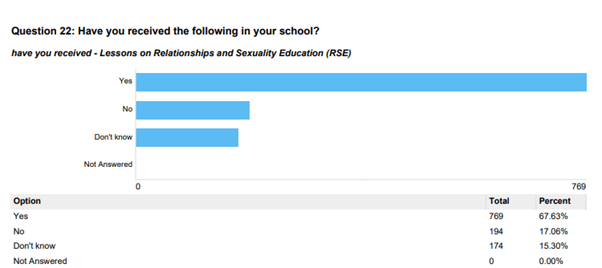

The question asks if pupils receive RSE lessons in school and over 67 % responded ‘Yes,’ 17% responded ‘No’ and over 15% of pupils were unsure. Youth Assembly Members discussed this and shared that not all schools term these lessons as RSE. Many of them had not heard of RSE until they joined the Youth Assembly.

The next few questions of the survey focused on the topics the committee felt were important to examine. See below for table of results:

Question | Yes | No | Don’t know |

Have you received lessons on sexism or women’s rights? | 36.24% | 43.80% | 19.96% |

Have you received lessons about healthy relationships? | 58.22% | 29.02% | 12.75% |

Have you received lessons on consent? | 51.89% | 28.94% | 19.17% |

The results were quite worrying as only 36% have received lessons on sexism or women’s rights in schools, only 58% have received lessons on healthy relationships and only 51% have received lessons on consent.

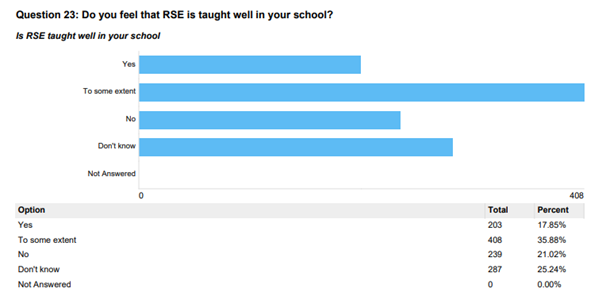

The next question examined the quality of RSE lessons within schools and how well pupils feel they are taught. 53% of pupils responded ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent’, when asked if RSE was taught well, whereas over one-fifth of pupils felt that RSE was not taught well in their schools. Moreover, over a quarter of pupils were unsure, which is rather concerning, as this could suggest that those pupils are not aware of what content they should be receiving in relation to RSE.

To further explore this question, pupils were asked to explain why they believe they receive a good quality education around RSE or not. Across school types and gender identities, pupils expressed mixed and often critical views on the quality, consistency, and relevance of RSE in Northern Ireland schools. Many felt it was under-taught, too basic, or delivered too late, often relying on outdated, religious, or fear-based messaging. A male pupil in a single-sex school remarked,

“We spent more time learning about seeds and cells than RSE… I’ve learned more from the NHS website.”

Others said RSE was “just something thrown at pupils during free periods” or simply “a ticked box.”

While a few pupils described good teaching,

“Our school talks about sex education quite a lot through LLW.”

The majority of respondents described RSE as superficial, focusing on biological facts and lacking content on healthy relationships, consent, LGBTQ+ inclusion, and women’s rights. A female pupil from a single-sex school noted,

“We have not been prepared for the real world… we lack basic information on safety, healthy relationships, abortion, LGBT+ issues.”

Another said,

“We’ve never been educated on safe sex — only on giving consent… mostly just told not to have sex.”

Many female pupils highlighted gaps in support, especially around contraception, relationship dynamics, and women’s health. One commented,

“I didn’t know the full extent of how a woman gets pregnant until I was 14.”

Another explained, “Everything is extremely surface level… nothing deeper than ‘no means no’.”

Male pupils often described RSE as something they could not recall or were not taught seriously: “I don’t know what RSE is” and “haven’t learnt in school about it yet” were common responses.

Religious influence was also cited as a barrier. One pupil explained,

“It was a VERY RELIGIOUS school… if the church didn’t approve, they didn’t do it.” Another added, “Catholic schools tiptoe around the subject and slightly shame those who do it.”

A few pupils from co-ed schools noted recent improvements: “Our class got taught about consent, safe sex, and the dangers of pornography — very beneficial.”

Others said the experience depended heavily on individual teachers and the maturity of the class.

Pupils consistently called for:

As one pupil summed it up:

“It’s a waste of time if we’re not actually taught what we need to know.”

The next question focused on the confidence of teachers facilitating lessons on RSE:

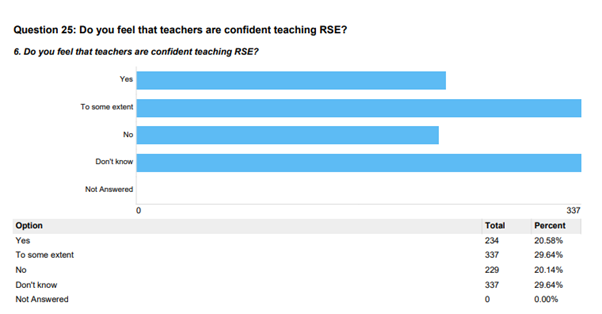

Over 50% answered ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent’ believing that teachers are confident teaching RSE. However, just under 49% either answered ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know.’ This could intimate that across the board, there is inconsistency in pupils’ experience of teachers who seem confident teaching RSE.

To further examine pupils’ reasons and experiences of this, a follow-up question asked, ‘why do you say that?’

Pupils across all school types expressed mixed views on whether teachers are confident and capable of delivering RSE. Many pupils felt that some teachers are well-trained and professional, with one male pupil stating,

“Because my teacher is qualified and knows what she is doing.”

Others noted,

“They’ve trained to teach — not sure why they wouldn’t [feel confident],” and “They speak with good clarity and confidence.”

However, a recurring theme was that RSE remains an uncomfortable or awkward topic for many teachers, especially when covering sensitive issues like sex, consent, LGBTQ+ inclusion, or periods. A female co-ed pupil observed,

“Many teachers seem to be uncomfortable talking about it, and they seem awkward, which makes the pupils feel more awkward.”

Another shared,

“They get awkward. Don’t answer questions. Skim through material.”

Several noted that teachers often rely on outside speakers to avoid teaching RSE themselves.

Some pupils reported that the delivery of RSE depends heavily on the teacher’s personality, beliefs, or gender. One male co-ed pupil commented,

“Female staff are happy to teach it… but male staff walk around stuff, even when it’s not awkward.”

A female pupil from a single-sex school added,

“In personal experience, while teachers may deliver the information, many act awkward and uncomfortable, which makes pupils feel embarrassed.”

Religious and cultural sensitivities were also identified as barriers. A number of pupils, especially from Catholic or religious schools, said teachers were hesitant or constrained in what they could teach. For example, one pupil shared,

“Catholic teachers can feel uncomfortable with the topic,” and another noted, “They focus on religion so much it’s ludicrous.”

Others pointed out that some teachers seemed to lack training or gave incorrect or biased information, such as a claim that birth control causes infertility, which was later disproven by a pupil’s parent who is a doctor. Several pupils noted that lessons often felt rushed or surface-level, with comments like,

“We were supposed to cover this content, but teachers felt too awkward,” and “It’s treated like a chore.”

Overall, pupils want teachers to be better trained, more open, and supported with proper resources. As one pupil summarised,

“It’s not that normalised, so they feel uncomfortable talking to kids and teenagers about it… better resources would help.”

The next question asked pupils if boys and girls were split up in RSE lessons for certain topics:

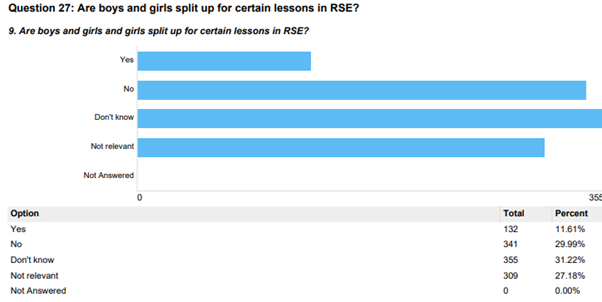

The results do not give a completely clear picture. Only 11% answered ‘Yes,’ whereas just under 30% answered ‘No’ with their experience of being split up for certain RSE lessons. However, over 31% of pupils were not sure and 27% stated that it was not relevant to them.

The next question was a follow-up question asking pupils if they answered yes, which topics they were split up for. Many pupils reported that RSE lessons were often gender-segregated, particularly in primary school, with girls learning about periods and “female puberty” while boys were taught about “male puberty.” A female pupil noted,

“Girls only learned about periods and ‘female’ puberty, while boys learned about ‘male’ puberty. There was no acknowledgement of any other experience of puberty.”

Another mentioned,

“For the period talk in primary school, the boys went into a different room.”

Content covered across groups included puberty, reproduction, body parts, menstruation, hormones, sexual health, and cancers like breast and testicular cancer. Some lessons were also combined with PE or anatomy topics, and several students highlighted the lack of shared understanding due to the split. One male co-ed pupil stated,

“Stuff for boys and girls is different, so they should be split up due to relevance”, while others expressed uncertainty or minimal recall of what was taught.

Overall, the responses reflect a common practice of dividing RSE content by gender, which may contribute to gaps in empathy, knowledge, and inclusivity.

The next two questions concentrated on gender stereotyped subjects within schools:

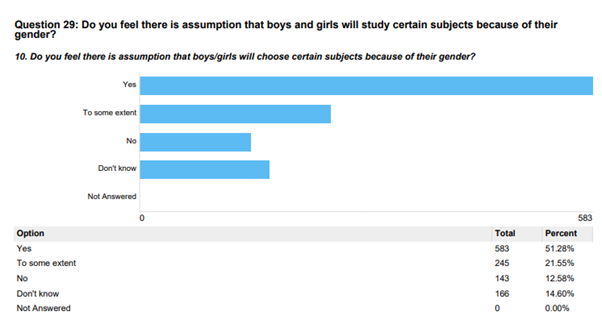

Nearly 73% of pupils answered with ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent’ in relation to the assumption that boys and girls will study certain subjects because of their gender. Although over 12% of pupils responded ‘No’ and over 14% were not sure. It could be suggested that the majority of pupils feel that there is an assumption that boys and girls will study certain subjects because of their gender.

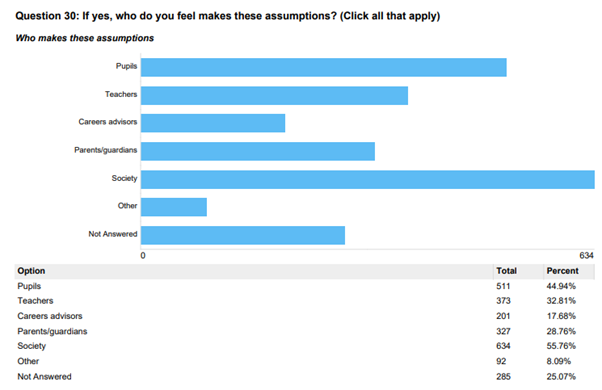

The follow-up question asked pupils ‘if yes, who do you feel makes these assumptions?’

To best reflect their answers, see below their answers in rank order:

The final question in this section asked pupils if they have any general comments in relation to young women’s rights in schools and the curriculum. Pupils across all groups highlighted issues of gender inequality, bias, and inconsistency within the school curriculum and wider school environment. Many described gender-stereotyped subject choices, with girls often underrepresented in STEM and boys discouraged from subjects like childcare or health and social care. One female co-ed pupil shared,

“STEM subjects could be geared towards females, and males could be more encouraged to do subjects such as RS or English,” while another noted, “Girls are not offered the same subjects as boys such as engineering or construction.”

Sex education and life skills were seen as biased or lacking altogether. Many pupils called for a standardised, inclusive RSE curriculum, taught without embarrassment and covering all genders equally. One pupil stated,

“All pupils should be taught the same material, with no exceptions… no one has anything to lose by learning about each other’s experiences.” Another added, “Sex education should be further prioritised,” and “The internet shouldn’t be teaching this stuff — schools should.”

School practices such as toilet access, PE, and subject guidance were also described as unequal. A male pupil pointed out,

“Boys need toilet passes while girls can go whenever,” and others noted that PE is still split along outdated gender lines. Several pupils expressed frustration that girls are often pushed into limited activities or discouraged from male-dominated spaces, while boys are not always taught about emotional intelligence or basic life skills like childcare.

There were also calls to address misogynistic influences, such as the spread of harmful online content from figures like Andrew Tate. One pupil said,

“It’s frightening to hear classmates idolising such openly misogynistic figures.”

Pupils across genders agreed that teaching about respect, consent, equality, and life skills from an early age is essential — both to tackle sexism and prepare young people for adult life.

In summary, pupils want:

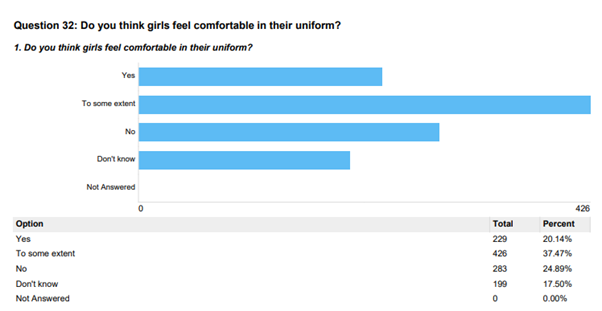

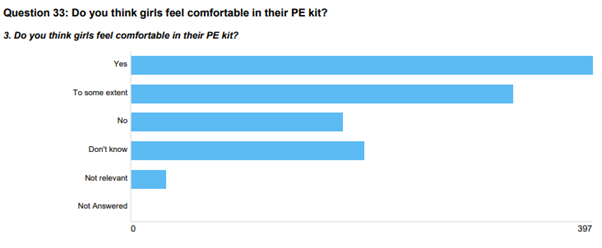

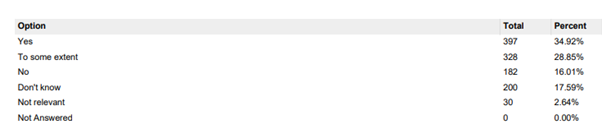

The next section of the survey focuses on school uniforms and PE kits due to the experiences that Members of the Youth Assembly Rights and Equality Committee were experiencing in their school life. The questions in this next section focus on girls feeling comfortable in their uniform, PE kits for girls, trousers as an option for girls, and gender-neutral uniforms.

When asked if think girls feel comfortable in their uniform, over 57% of pupils replied with ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent.’ Almost a quarter said ‘no.’

When asked if think girls feel comfortable in their PE kit, over 62% of pupils replied with ‘Yes’ or ‘to some extent’ which was slightly higher than for uniform.

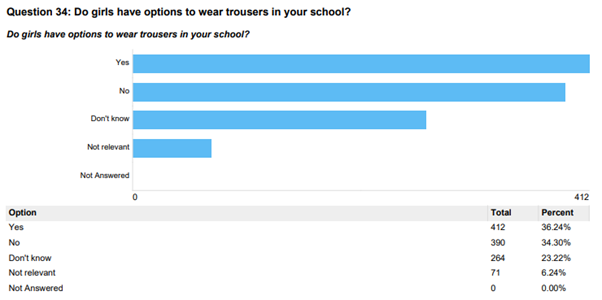

The question resulted in a mixed response from pupils as over 36% responded ‘Yes’, over 34% responded with ‘No’ and 23% of pupils also replied that they were unsure.

Gender neutral school uniform can be defined as clothing rules at school that do not depend on whether you are a boy or a girl. Instead of saying “skirts for girls” and “trousers for boys,” everyone gets the same options and can choose what they feel most comfortable in, no matter their gender. It’s about freedom, fairness, and inclusion.

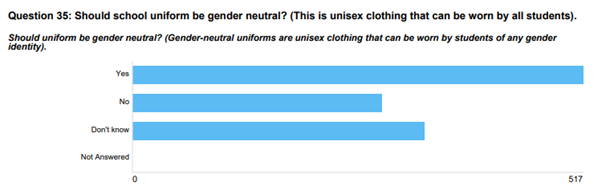

In relation to the above question, nearly half of the responses from pupils answered ‘Yes’ to gender neutral clothing, although a quarter of pupils responded ‘No’ and 29% stated that they were not sure. This could suggest that most pupils would like to see gender neutral options for school uniforms.

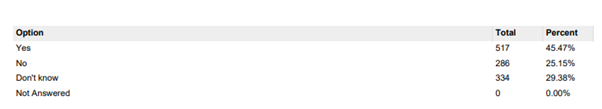

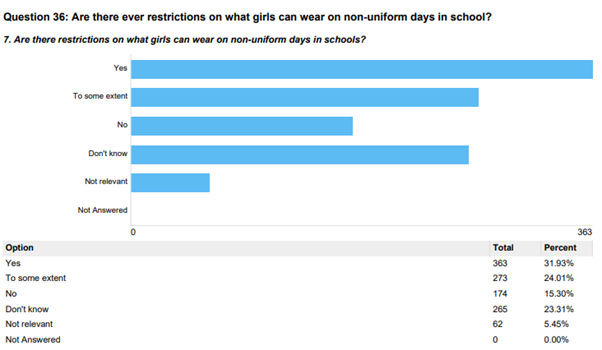

Through discussion and workshops with Members of the Youth Assembly’s Rights and Equality Committee, we discovered that some girls faced restrictions on what they could wear on non-uniform days. For example, some stated that they were not allowed to wear leggings, crop tops or low-cut tops. The majority of pupils who responded to this question have echoed this. Nearly 56% of pupils responded with ‘Yes’ and ‘to some extent’ in relation to restrictions to girls’ clothing on non-uniform days in school. However, over 15% of pupils stated ‘No’ and over 23% responded that they were uncertain.

A follow-up question asked if pupils had any further comments about girls and school uniforms and many pupils expressed that current school uniform policies are outdated, uncomfortable, and unfairly enforced, particularly along gender lines. A common theme was the desire for choice rather than a single gender-neutral uniform. One pupil said,

“Gender neutral uniforms are a bad idea. Uniform options, however? Yes!”

Others highlighted how rules disproportionately affect girls, with one commenting,

“Girls have to wear these horrible, itchy tights… I have to spend all day pulling them up,” and another stating, “There is too much focus on skirt length and not enough on a comfortable uniform that makes girls feel confident.”

Several students shared that wearing trousers as a girl often leads to judgement, saying,

“If we choose trousers, people assume we’re lesbian or trans,” while another pointed out, “Girls are allowed to wear trousers, but it often results in people calling them lesbians or tomboys.”

Transgender pupils, especially in single-gender schools, felt excluded; one student said,

“It is a joke especially for trans students in all-girl schools.”

Boys also questioned double standards, with one asking,

“If a girl can wear trousers in school, why can’t a guy wear a skirt?”

Cost and comfort were repeated concerns:

“They need to be affordable and cheap,” and “It’s itchy, heavy, uncomfortable, pointless.”

While some valued uniforms for equality and safety, the strongest message across the responses was clear: pupils want the freedom to choose what makes them feel safe, comfortable, and respected, without being judged or punished for it.

The next section of the survey focused on policies within schools and the potential impact of school policies on girls. This section also concentrates on the Ending Violence Against Women and Girls strategy.

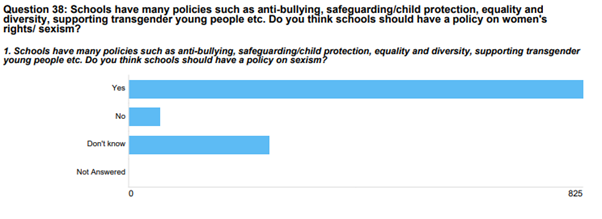

The overwhelming majority of pupils (72%) believed that their schools should have policy on sexism. However, over 22% were unsure and 5% felt that schools should not have a policy on sexism.

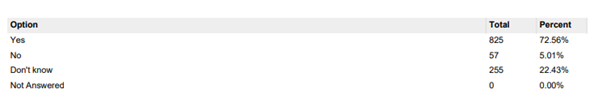

When asked if their school had a policy on sexism only 91 pupils stated that their school had such a policy. Furthermore, over 27% of pupils answered ‘No’ to the question and over two-thirds of pupils were unsure. Interestingly, 64 % said they didn’t know so even if such a policy exists, pupils are unaware of it.

The next two questions in the survey were open-ended, follow up questions:

In relation to the first follow-up question on the impact of a young women’s rights policy in schools, views were mixed, with many uncertain if such policies even exist. A common theme was a lack of awareness:

“I genuinely have no clue if it has one and I’ve been there for 6 years” and “If there is a policy it hasn’t been shared with us students.”

In boys’ schools, relevance was questioned:

“No girls in this school” and “Don’t know.”

Some acknowledged issues like sexist remarks:

“Boys often make comments; they aren’t told the negative effects of it.”

In co-ed schools, some pupils noted minimal or no impact:

“There hasn’t been any impact at all,” and “If they do it doesn’t impact any pupils’ day to day life.”

Others reported more positive outcomes:

“It has helped people to understand women’s rights better” and “Various bodies have been set up to improve the experience for female students.”

However, inconsistency in responses to sexist behaviour was noted:

“I have never seen a boy punished for sexist comments before” or “Students will get a punishment if it is reported.”

In girls’ schools, some felt empowered:

“It has greatly impacted the confidence of pupils and thus academic performance” and “We talk about it all the time in lots of subjects.”

Yet uncertainty still existed:

“I don’t think we do but I’m not sure.”

Some highlighted positive peer support:

“We try and build up each other and become women activists instead of being against each other all the time.”

Others mentioned practical steps, like:

“We got pads and tampons.”

Overall, responses suggest varied experiences and a need for clearer communication and consistent enforcement of gender equality policies.

In relation to the last question, asking pupils to contribute general comments about policies, pupils across different school types expressed frustration at the limited impact and visibility of school policies on sexism, gender equality, and inclusion. A common concern was that policies are either not implemented effectively or ignored altogether:

“No policy is listened to” and “The school policy is good, but students rarely listen to it, so it’s got to come down harder.”

Some felt policies existed in name only:

“Anti-bullying policy is there yet bullying happens every day,” and “I think it should be much easier to find a full written school policy if a student should wish to.”

Others shared that sexist behaviour goes unpunished:

“The boys just get away with it” and “Most bullying goes on behind the backs of teachers.”

There were calls for stronger enforcement:

“School policy should come down hard on foul sexual language” and “There needs to be a clearer, definite statement from all schools that they will not tolerate sexism.”

Several pupils said school leadership fails to take pupil voice seriously:

“They claim to listen and pretend to give pupils a voice but then completely ignore any issues brought up.”

Suggestions included broader inclusivity:

“There should be stuff about men too and their struggles” and “We can’t risk excluding men and LGBT+ people from the conversation about sexism.”

Personal accounts also highlighted failures in safeguarding and support:

“I used to be bullied and catcalled… they simply continued messing with me, even when they received sanctions,” and “Policies do very little for transgender youth.”

Others called for more practical changes like uniform flexibility:

“ALLOW GIRLS TO WEAR TROUSERS,” and “Very small differences, such as just asking pupils’ pronouns, can have huge impacts.”

Overall, pupils called for genuine commitment, inclusive policies, better enforcement, and meaningful engagement with their lived experiences.

This section of the survey asked pupils about their awareness of the EVAWG strategy.

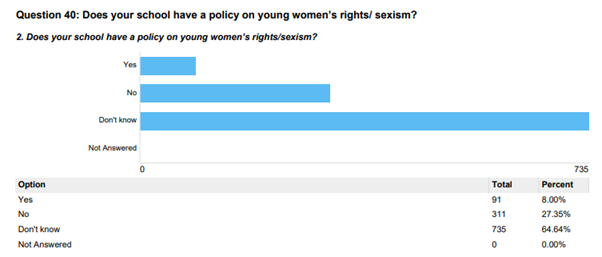

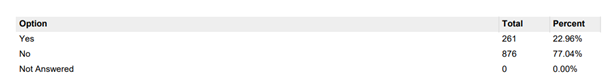

The above question asked pupils about their general awareness about the new strategy released September 2024. It is clear from the information above that very few pupils are aware of the strategy as over 77% of pupils responded ‘No,’ whereas only just under 23% of pupils were aware of the strategy.

The next set of questions asked pupils if they agreed with the aims of the EVAWG strategy and are summarised in the table below:

Aims | Yes | No | Don’t know |

Everyone will understand what violence against women and girls is | 81.71% | 4.49% | 13.81% |

Everyone will be empowered to enjoy healthy, respectful relationships | 83.73% | 4.31% | 11.96% |

Organisations will place importance on the prevention of violence against women and girls so that women and girls are safe and feel safe everywhere | 81.09% | 3.25% | 15.66% |

There are high-quality services for women and girls who are victims and survivors of violence | 74.23% | 4.66% | 21.11% |

We will have a justice system which is trusted by everyone to address violence against women and girls | 77.66% | 4.22% | 18.12% |

All of government and society will be working better together to end violence against women and girls | 78.19% | 4.31% | 17.50% |

Parents, carers, and those who work with young children will help to prevent violence against women and girls by modelling respect and equality in relationships and addressing harmful gender stereotypes | 80.91% | 2.90% | 16.18% |

It is clear that most pupils agreed with the aims of the EVAWG strategy. Most pupils responded ‘Yes’ to each of the aims, with a high percentage of respondents at a rate of 70% upwards.

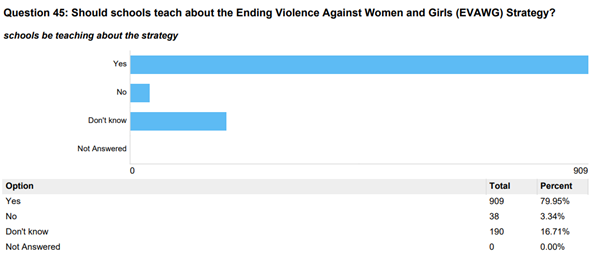

Due to the high responses from the previous questions on the aims of EVAWG, when pupils were asked if schools should teach about the EVAWG strategy, the majority responded ‘Yes’ as nearly 80% of pupils felt it was important.

The last question on EVAWG asked pupils if they had any further comments about the strategy which are summarised below.

Pupils generally welcomed the Ending Violence Against Women and Girls (EVAWG) strategy, recognising its importance and calling for it to be implemented across all schools. Many described it as,

“a good step forward” and said, “it’s about time,” with some expressing urgency: “It should immediately be brought into schools across the country with the number of women being murdered in our country.”

Several pupils shared personal or peer experiences of harassment, fear, and violence—both in and outside school—stating, for example,

“My friends and me have been touched and shouted at walking up the town after school” and “I have friends my age scared to walk home at night.”

Despite support, many felt the strategy should go further by addressing violence and sexism experienced by all genders. Pupils stressed that, “Sexism affects everyone” and that violence against boys, LGBTQ+ pupils, and neurodivergent young people is often overlooked.

Comments like “not dismissing that girls and women do face sexism and abuse but boys do too” and “violence in general should be fought against” reflected a desire for the strategy to be more inclusive.

There was broad agreement that schools should play a key role in tackling gender-based violence, with calls for better and earlier education:

“Teach in every single secondary school and tertiary education too regardless of gender makeup.”

However, pupils also highlighted significant gaps in delivery and awareness, with some stating they had…

“Never been taught about it” or “never really heard of it.”

While many supported the idea of school involvement, others were sceptical about impact, warning that “assembly talks are always jarring” and that teachers may “rush through things like this.”

Pupils emphasised the need for cultural change, particularly in attitudes among boys and men. Several believed that harmful behaviours are normalised and unchallenged, such as hearing pornographic language or facing online harassment, with one pupil noting,

“Violence can be being forced to listen to verbal pornographic language all day long… it makes us depressed.”

Others stressed that simply “raising awareness” is not enough – what is needed is real accountability and long-term change in attitudes and behaviour:

“Men just don’t care enough… they are influenced by society to believe the woman must have deserved what happened.”

Overall, pupils viewed EVAWG as a necessary and promising initiative but stressed that for it to be effective, it must be understood by all pupils, inclusive, well-taught, and grounded in real change – not token gestures.

The final section of the survey asked pupils for their general comments about the survey, if anything surprised them and what schools could do to tackle the problem of sexism in schools.

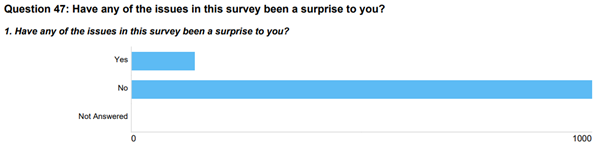

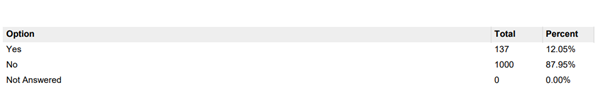

The overwhelming majority of pupils responded to the above question, asking them if anything in the survey surprised them, with nearly 88% stating ‘No.’ Whereas 12% of pupils responded ‘Yes.’ Overall, this could suggest that most pupils are very aware of the current issues surrounding sexism in schools. The follow-up question asked pupils who responded ‘Yes’ to go into more detail.

Some pupils found the survey questions surprising, with several noting that the issues raised were either entirely new or rarely discussed in their schools. As one pupil put it,

“70 percent of partaken questions in this survey really surprised me the most,” while another said, “All of them because some teachers don’t really care about problems there can be with girls and women.”

A recurring theme was lack of awareness:

“I’ve never heard of the RSE or the strategy,” and “We don’t get taught about these issues.”

Some pupils commented that they had not realised the scale of gender-based issues until prompted by the questions:

“They’re not necessarily issues I haven’t heard about, but I’ve been unaware of the scale of them.”

A number of male pupils, particularly from all boys’ schools, expressed confusion or discomfort, feeling the survey did not apply to them. Comments included:

“I go to an all-boys school, how am I supposed to know any of this?” and “As a male I do not think I should comment on girls’ periods.”

Some felt the questions were too focused on girls:

“Too many girl questions and gets too annoying and stupid,” while others reflected on the lack of teaching:

“I never knew that society wanted to promote women’s equality and well-being.”

For co-educational and girls’ schools, surprises ranged from specific topics—like

“Locker room talk,” “uniform policies,” and “the amount of violence girls go through”– to broader reflections on unequal treatment. One pupil observed,

“Girls are treated a lot differently than boys are in schools,” while another said,

“Just all the policy stuff and the questions about what we should’ve been taught.”

Some pupils acknowledged never having considered these issues in depth before:

“Thinking about the negligence of women’s rights and sexism values in comparison to anti-bullying, really. Never really questioned it before.”

Across all groups, the survey prompted reflection on gaps in education and awareness around gender-based violence, sexism, and policy. Even where pupils had some prior knowledge, many said they had not grasped the full impact:

“Lots were things I was aware of, but not until I fully thought about what exactly they were did I realise how prevalent they are.”

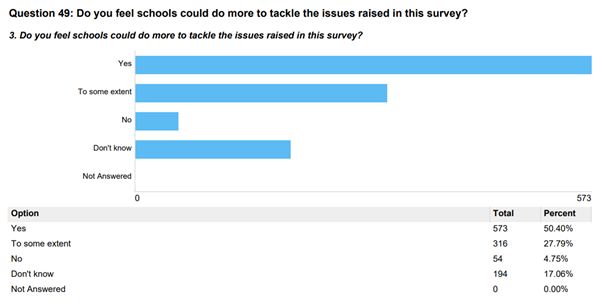

The majority of pupils, 50%, answered ‘Yes’ when asked if schools could do more to tackle to issues raised in the survey. Furthermore, over 27% stated ‘to some extent,’ implying that more could be done in schools. However, over 17% were unsure and just under 5% responded ‘No.’

A follow-up question asked what schools could do in this instance and 79 pupils responded.

Overall, the survey prompted many to reflect on the gaps in their education and the lack of open conversations around sexism, violence, and women’s rights. As one pupil summed up,

“All of them [questions]… because some teachers don’t really care about problems there can be with girls and women.”

Finally, the last question asked pupils to give their general comments about the issues raised in the survey. Many pupils found the survey deeply surprising, not necessarily because they disagreed with the content, but because the issues raised were so rarely acknowledged in their everyday school life. A significant number of students revealed that they had never been taught about gender-based violence, women’s rights, or equality strategies in school. Comments like,

“I didn’t know about the women’s rights scheme” and “All of them [questions] as I never knew what the survey was about, and we don’t get taught about these issues” highlight how unfamiliar these topics are too many.

For some, it was their first encounter with the idea that schools or wider society were even trying to address gender-based inequality. Many boys, particularly those attending all-boys schools, expressed confusion or frustration at the nature of the questions, often suggesting that they felt excluded or that the survey focused too heavily on female experiences. These reactions suggest a clear gap in inclusive, gender-aware education that would help boys understand why such questions matter and how they are part of broader conversations about respect, safety, and equality.

Despite initial resistance, some pupils showed reflection and growing awareness. One said,

“The issues were a surprise because in my school none of them exist; both girls and boys do bad things.”

Others were shocked by the scale of violence girls experience, particularly outside of school settings:

“The amount of violence girls are put through” and “My friends and me have been touched and shouted at walking up the town after school.”

Additionally, some students criticised the lack of attention given to boys’ experiences and raised concerns about exclusion. One asked,

“Why was there nothing about boys?” while another wrote, “They’re heavily exaggerating a lot about women.”

These responses show a need for gender equity education that recognises the specific risks women and girls face while also including boys in the conversation in meaningful ways.

Overall, the survey highlighted a widespread lack of awareness and education around issues of gender, safety, and respect. For many, it was their first time encountering such topics in a structured way. While some pupils reacted with discomfort or defensiveness, others began to engage thoughtfully, suggesting that when taught with care and context, these discussions can help pupils of all genders better understand the realities their peers face. As one pupil summed up,

“I think the things they’re standing for are pretty good – we just need to hear more about them in school.”

Across all school types, pupils, particularly girls, reported frequent exposure to sexualised comments, harassment, and misogynistic jokes, often dismissed by staff as normal behaviour.

“When I was in third year, the boys in our class started making rape jokes when in class. The teacher was male and ignored the comments. But they stuck with me ever since.”

— Co-Ed Female

“The boys in my year group have ranked the girls and even labelled some as someone they would wish to sexually assault. Little was done by our school to investigate this.”

— Co-Ed Female

“I’ve experienced about 10 boys standing either side of a corridor who shamed girls when they had to walk through, whether it was about their appearance or something about them.”

— Co-Ed Female

“Many interactions with boys involve subtle sexist behaviour presented in a socially acceptable guise. Despite this, the negative impact on women remains significant.”

— Co-Ed Female

“When Andrew Tate came along, all the boys, older and younger, were copying him & it made me really uncomfortable.”

— Co-Ed Female

“Some boys tend to target girls and make them feel uncomfortable and unsafe. The boys think it’s normal and okay to make sexist remarks.”

— Co-Ed Prefer Not to Say

A significant number of pupils, including girls in all-girls schools, raised concerns about inappropriate remarks, gender bias, and teacher complicity in harmful dynamics.

“There were rumours of one male teacher pretending to drop something so that he could look up girls’ skirts.”

— Co-Ed Female

“Male teachers treat male pupils better and vice versa with female teachers.”

— Co-Ed Female

“Teachers remarking on skirt length stating they can see ‘the whole picture’ and saying ‘I can see my bum’ — it’s still sexually explicit even if it comes from a female teacher.”

— Girls Only Female

“Teachers expect girls to behave better, but reward boys for doing the bare minimum.”

— Co-Ed Female

“Some teachers assume boys can do better than girls, so they don’t give the same opportunities.”

— Co-Ed Female

“When I wanted to move to Politics for A-Levels, the school assumed it was because there were boys in the class. They disregarded my academic interest.”

— Girls Only Female

Girls in both co-ed and girls-only schools described excessive control over their clothing and appearance, often tied to the assumption that they are responsible for male reactions.

“Being told to cover up skin — skirt length being a large topic of conversation while boys can wear shorts.”

— Co-Ed Female

“When grown adults are commenting on your appearance/skirt length this makes us uncomfortable — we are children.”

— Co-Ed Female

“I find myself subconsciously pulling my skirt down because teachers have said ‘the boys don’t like it.’”

— Co-Ed Female

“The ‘uniform checks’ are a major concern — girls have to kneel in the corridor to check skirt length in front of others.”

— Girls Only Female

“If your skirt is long, you’re weird. If it’s short, you’re ‘suggestive’ — there’s no way to win.”

— Girls Only Female

“Girls get shouted at for hair, makeup, skirt length, jewellery — boys just get a warning.”

— Co-Ed Female

Girls described embarrassment, lack of access to products, and dismissive attitudes from staff and male pupils around menstruation.

“Girls shouldn’t be forced to say they have their period out loud in order to be allowed to leave — it’s embarrassing.”

— Co-Ed Female

“We’re told we can’t go to the bathroom twice in a day because the teacher thinks we’re vaping — not bleeding.”

— Co-Ed Female

“Even when restocking toilets with pads, we act like it’s a secret or shameful.”

— Co-Ed Female

“If a girl is in pain, teachers often say physical activity will help — which can feel patronising.”

— Co-Ed Female

“We were taught more about seed germination than puberty or periods. I had to learn from the NHS website.”

— Boys Only Male

Many pupils described inadequate, outdated, or religiously constrained sex education which failed to address real-life issues like consent, boundaries, or healthy relationships.

“They just get an outside organisation to do a quick talk every now and then, and that’s it.”

— Boys Only Male

“We’re taught about pregnancy and STIs, but not about what’s right or wrong in a relationship, or how to respect boundaries.”

— Co-Ed Female

“One boy said he’d rape a girl in his form class — after all the lessons about consent.”

— Co-Ed Female

“I’ve learned more from the NHS and online than I ever did in school.”

— Co-Ed Female

“RSE was heavily censored in our religious school. Anything not church-approved was skipped.”

— Co-Ed Female

The lack of effective reporting systems, combined with a culture of disbelief or minimisation, could suggest a widespread sense of unsafety and resignation.

“I’ve tried to approach staff about this issue, but they pretend we don’t need protection from foul, sexually depraved language from boys.”

— Co-Ed Female

“When I’ve received sexual comments and groping in the past, even when I told someone, all the boy got was a call home — no real punishment.”

— Co-Ed Female

“When we report unwanted advances, we’re told: ‘boys will be boys.’”

— Co-Ed Female

“Girls are seen as snitches if they talk about sexist comments made to them — it’s incredibly harmful.”

— Co-Ed Male

The Youth Assembly Rights and Equality Committee, in producing this report, have considered the research, spoken to the experts including young people and have arrived at the following recommendations:

Pupils consistently called for schools to take a more proactive role in addressing the underlying attitudes that fuel sexism. They want equality to be taught not just in policy statements but through structured education that challenges harmful norms. Schools should explicitly teach respect, consent, and emotional expression across all genders, including respect for female teachers. Parents and caregivers also play a key role, and schools should involve them through workshops or communications to reinforce shared values.

Many pupils expressed frustration with uniform rules that disproportionately target girls or reinforce outdated gender expectations. They want uniforms which are comfortable, inclusive, and fair, particularly in hot weather or during puberty, when discomfort can be acute. Uniform enforcement should be handled sensitively, and schools should shift the burden away from girls by focusing on respectful behaviour of students and staff rather than policing clothing choices.

A clear concern was the lack of action when pupils report sexist, racist, or inappropriate behaviour including incidents involving staff. The current systems are seen as opaque, inconsistent, and ineffective.

Pupils want safe, transparent, and trusted mechanisms for disclosure. This should include anonymous reporting options, clear follow-up procedures, and designated staff members who are visible and trained to respond appropriately.

While many pupils supported targeted efforts to end violence against women and girls, there was also a call to ensure that violence experienced by boys and gender-diverse pupils is acknowledged too. Several pupils also spoke to the compounded effects of facing both racism and sexism, and the lack of appropriate staff responses. Schools should ensure that anti-discrimination policies address overlapping forms of harm, and that staff are trained to understand how gender, race, and identity interact. Inclusive curriculum materials, better representation, and clearer disciplinary procedures are all needed to address these gaps. This would help avoid alienating any group while ensuring that those most at risk receive focused protection and support.

Pupils raised concerns about the influence of online personalities who promote misogynistic ideas, which they see being echoed in school culture. Schools should introduce digital literacy lessons that help pupils critically evaluate online content, challenge harmful narratives, and foster respectful relationships. There should be targeted efforts to engage boys in these discussions and provide alternative models of masculinity and leadership.

Pupils want schools to create a culture where equality and inclusion are visible in everyday actions — not just in posters or assemblies. This includes holding pupils and staff accountable for discriminatory behaviour, offering meaningful opportunities for pupil voice, and building a curriculum that reflects diverse experiences. Real change, from the pupils’ perspective, will come when schools align their stated values with consistent and visible practice.

The committee recommends that schools introduce a comprehensive sexism policy (distinct from an Anti-bullying policy) to foster a safe, inclusive, and respectful environment for all students. This policy would serve to prevent and address gender-based bullying, harassment, and discrimination, ensuring that all students are treated equally, regardless of gender. It would provide clear guidelines for staff and students on identifying and responding to sexist behaviour, while promoting positive attitudes towards gender equality. By challenging harmful stereotypes and creating a culture of respect, this policy will not only safeguard students and staff but also empower them to actively participate in creating an equitable learning environment. Additionally, such a policy would support the school’s broader commitment to student well-being and the development of socially responsible individuals.

The committee recommends that schools integrate youth voice into the development and implementation of policies related to young women’s rights. By actively involving students in discussions and decision-making processes, schools can ensure that their unique perspectives, needs, and experiences are considered. This approach not only empowers young women but also fosters a more inclusive environment that supports gender equality. Engaging students in shaping policies on issues such as gender-based violence, sexual harassment, and equal opportunities will help schools create more responsive and effective measures. Additionally, it encourages a culture of respect, understanding, and active participation, ensuring that young women’s rights are advocated for in a way that truly reflects their views and concerns.

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to the following individuals for their time, insight, and support in contributing to our work on gender equality and young people’s rights:

Your contributions have been invaluable in helping us explore, understand, and act on the issues that matter most to young people today.